Leading and Managing Change

© DR Phelan - Uplift Centre 2025

Tools for when you’ve got a particular change goal in mind

6 models to consider when implementing change; 8 common errors; and a 9 step summary for managing a successful change project.

See also our resources on: Adaptive versus Technical Change and Triple Loop Learning in New Thinking Required ; Understanding Change- what happens to us and others when we’re hit with change; Organisational Development - Change Models

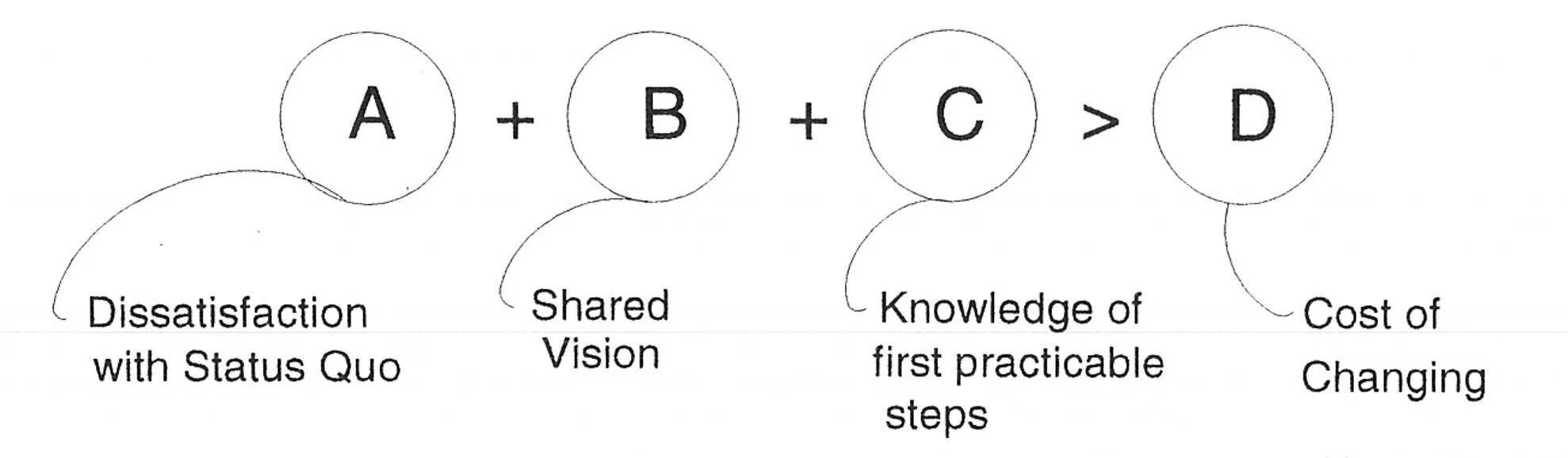

1. Change Occurs when A + B + C > D

The original “Formula for Change” was described by David Gleicher in the 1960s; then in the 1980s by organisational theorists Richard Beckhard and Reuben Harris, and later in the 1990s by Kathie Dannemiller.

Formula for Change

A. People won’t change unless they are dissatisfied. So many change efforts fail because people are actually ok with the way things are. Change begins by galvanising people’s discontent with the way things are i.e. “rub raw the wounds of discontent”.

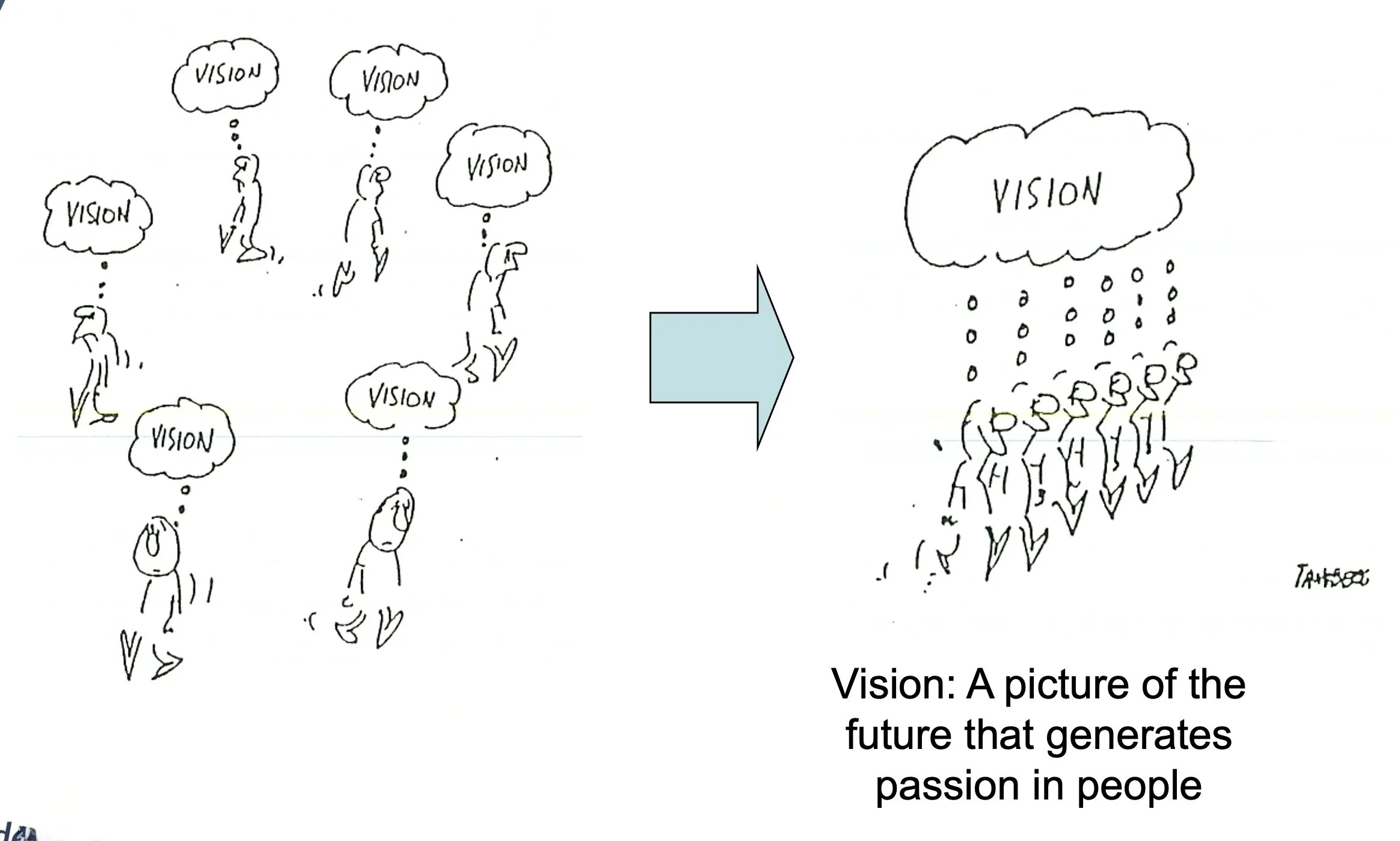

Cartoons by Ron Tanberg

B. Then contrast what is not working with a shared vision of a desirable future that everyone wants. e.g. The Israelites were slaves in Egypt. Moses described a picture of the promised land flowing with milk and honey.

C. People also need to know what the next steps are that will take them towards the desired future. e.g. Moses instructed the Israelites to prepare for a swift, yet organised departure by following specific Passover preparations and packing quickly for their journey, including taking their unleavened dough and other belongings.

D. People have to see that the benefits of leaving or changing their current unsatisfactory situation, outweigh the cost of changing i.e. that it is going to be worth it. All change involves loss or leaving behind something, even if its fond memories. There is always some cost of change.

Why useful: It’s a simple tool to use when you want to make a change. As a leader you may see the benefits of changing something. However, if those affected are not dissatisfied with the current situation, they will resist. It is useful to ask yourself as a leader: A: Are people dissatisfied with the current situation? B: Have you clearly painted the picture of what the new setup will be like? C: Is everyone clear on what is going to happen next and what steps they need to take? And finally, D: Have you made clear why the change will be better i.e. what’s in it for them?

So the level of Dissatisfaction + shared Vision + clear First Steps must outweigh the level of Resistance or Cost of changing.

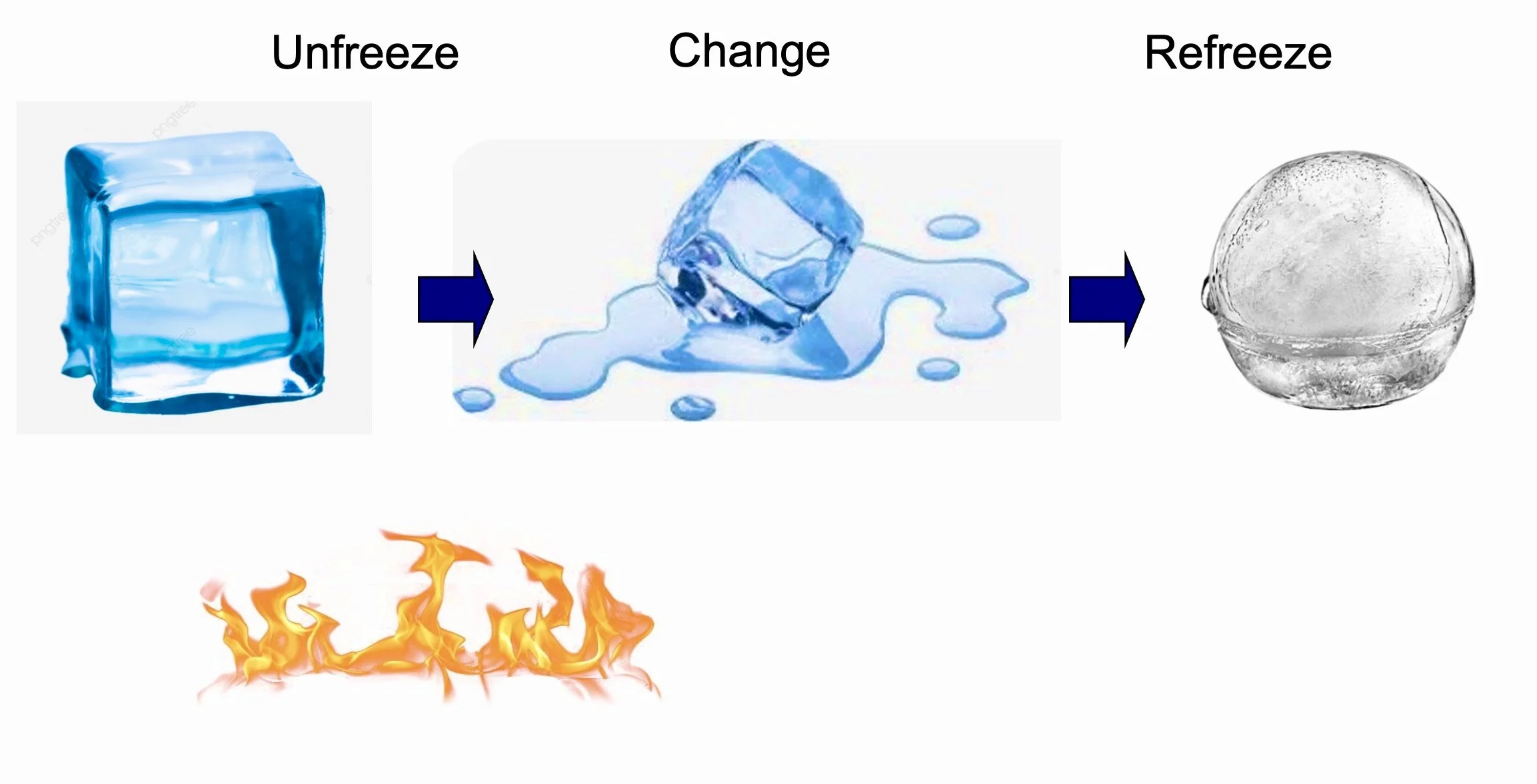

2. Lewin’s Three-Stage Model

Kurt Lewin’s three-stage model of change likens it to changing an ice cube into a different shape through unfreezing, changing and refreezing. Change begins with disrupting the status quo, then introducing new behaviours/ways of working, and finally stabilising them.

Unfreezing: The initial phase involves dismantling existing mindsets or structures, a prerequisite for overcoming inertia. Those involved come to recognise the need for something to change; it involves examining the status quo, increasing the drivers for change and decreasing the resistance to change;

Change : Next comes the transformative period, marked by uncertainty and transition, where old ways are replaced with new paradigms. New ideas are tested and new ways of working emerge; and

Refreezing: Finally, the "refreeze" stage crystallizes the new norm, fostering comfort and stability. New behaviours, skills and attitudes are stabilised and commitment to change is achieved.

For change to occur, there must be an “unfreezing” or disruption to the current comfort zone. And the desired new state has to then be reshaped, held in place, and “refrozen”.

Why useful: It’s simple and foundational— developed in the 1940s, many later models build on it.

3. Kotter’s 8-Step Change Model

Harvard professor and change management expert John Kotter created the 8-step process for leading change. Kotter’s theory focuses primarily on the people involved in a change process and their psychology. He divides it into eight steps:

John Kotter’s The 8 Steps for Leading Change

Create a sense of urgency. Motivate people to act.

Build a guiding coalition of committed people to guide, coordinate, and communicate activities.

Form A Strategic Vision. Clarify how the future will be different from the past and get buy-in for how you can make that future a reality through initiatives linked directly to the vision.

Enlist a volunteer army. Large-scale change can only occur when massive numbers of people rally around a common opportunity. At an individual level, they must want to actively contribute.

Enable action by removing barriers. Remove the obstacles that slow things down or create roadblocks to progress. Clear the way for people to innovate, work more nimbly across silos, and generate impact quickly.

Generate Short-Term Wins. Wins are the molecules of results. They must be recognized, collected, and communicated – early and often – to track progress and energize volunteers to persist.

Sustain Acceleration. Press harder after the first successes. Your increasing credibility can improve systems, structures and policies. Be relentless with initiating change after change until the vision is a reality.

Institute Change. Articulate the connections between new behaviors and organizational success, making sure they continue until they become strong enough to replace old habits.

Why useful: Widely used in organisations; highlights leadership, communication, and culture.

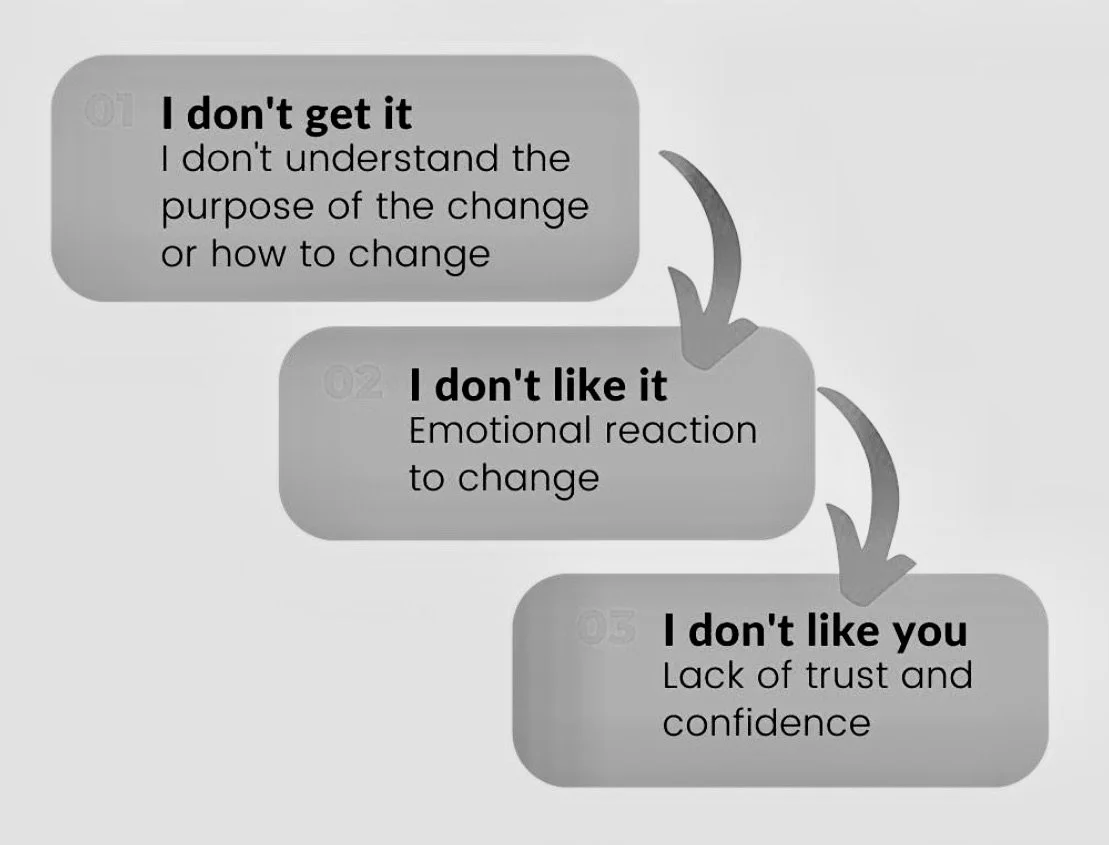

4. Resistance to Change Model

Maurer (1996, expanded in Beyond the Wall of Resistance) identifies three levels of resistance that leaders need to recognise and address differently:

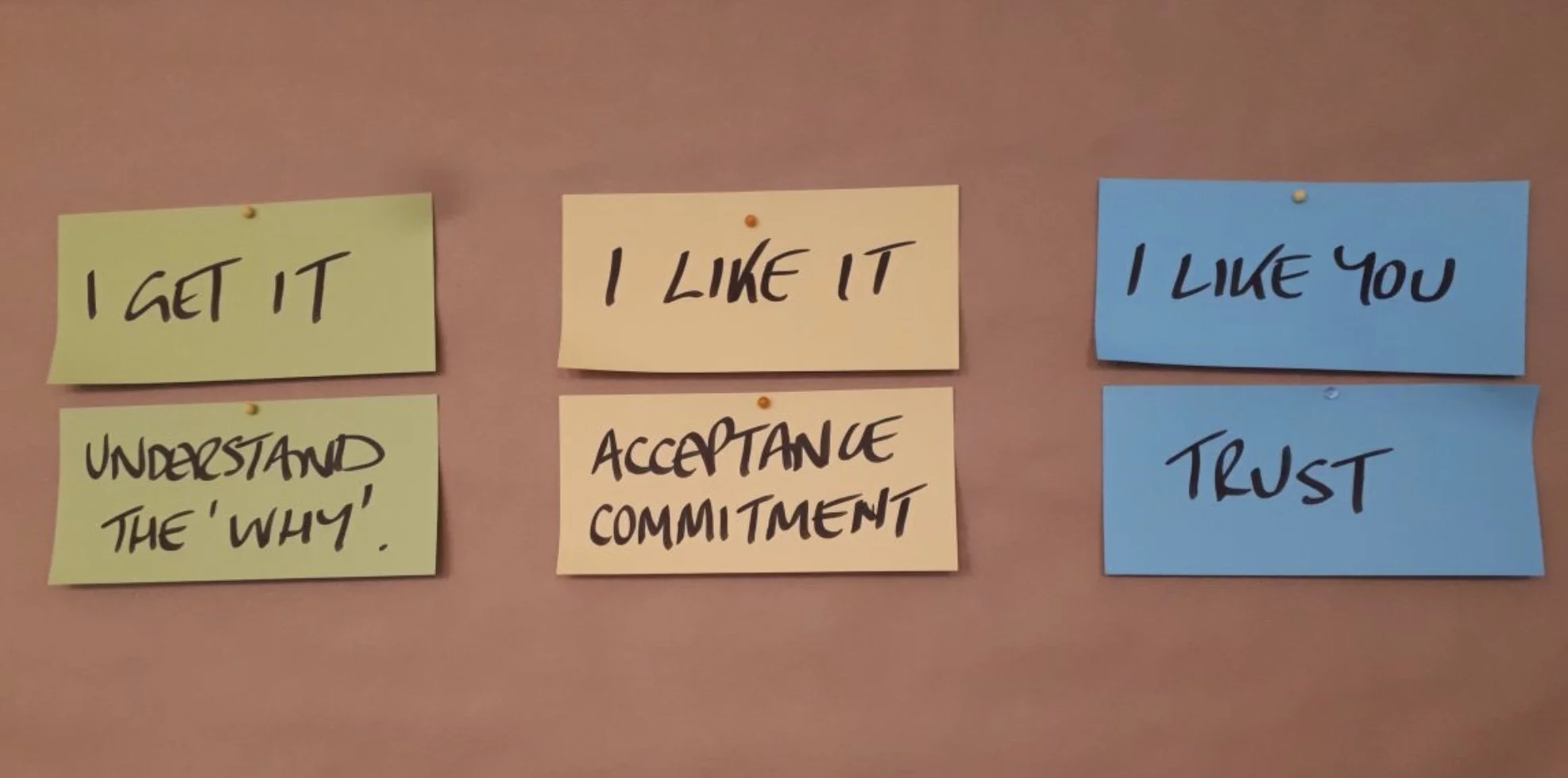

The Maurer 3 Levels of Resistance and Change Model

Level 1 — “I Don’t Get It”

Nature of resistance: Rational/cognitive objections. People don’t understand the change, disagree with the evidence, or are simply confused.

Leader mistake: Assuming all resistance is Level 1 and overloading people with more data, logic, and PowerPoint slides.

Approach: Provide clear, tailored explanations, ensure transparency of information, and invite questions.

Level 2 — “I Don’t Like It”

Nature of resistance: Emotional resistance, often rooted in fear of loss (status, face, control, comfort). It can provoke fight-or-flight reactions.

Impact: Emotions block rational thinking, reduce trust, and can paralyse communication.

Approach: Acknowledge fears, show empathy, highlight benefits, and actively engage people in shaping the change.

Level 3 — “I Don’t Like You”

Nature of resistance: Relational/personal — distrust of the leader, organisation, or past experiences. Even if people understand and accept the idea, they resist who is leading it.

Impact: Deep mistrust can make resistance entrenched and toxic.

Approach: Rebuild trust by demonstrating honesty, following through on promises, investing in relationships, and sharing power where possible. help people to see “you’re on our side” / “you’re one of us”.

Maurer’s Guidance for Overcoming Resistance

Make a compelling case for change: Show why it matters, beyond slogans.

Tailor communication: Adapt to different audiences’ needs and learning styles.

Emphasise benefits and engage employees: People support what they help create.

Build trust: Be consistent, keep commitments, and listen actively.

Stay open to feedback: Adapt and refine the change based on input.

Why it’s useful

Reminds leaders that resistance is not the enemy — it’s often a signal of poor communication, weak trust, or unaddressed fears.

Equips leaders with a diagnostic lens to identify which level of resistance they’re facing and respond appropriately.

Encourages humility: leaders must look at their own credibility and relationships, not just “fix” employees.

5. Nudge Theory (Thaler & Sunstein)

Outlined in their book Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein argue that people’s decisions are often shaped by choice architecture—the way options are presented. Instead of relying on commands, penalties, or heavy persuasion, leaders can design environments that nudge people toward better choices without removing freedom.

Core Idea

People are not perfectly rational decision-makers. They rely on shortcuts, habits, and biases.

Subtle changes in context (the way choices are structured) can significantly influence behaviour.

A nudge is any aspect of the choice architecture that alters behaviour predictably without forbidding options or significantly changing economic incentives.

Key Principles of Nudges

Defaults matter: People tend to stick with default settings (e.g., opt-out option rather than opt-in).

Simplify choices: Too many options can overwhelm; fewer, clearer choices guide better outcomes.

Use social proof: People are influenced by what others do (“90% of guests reuse their towels”).

Highlight consequences: Make the cost/benefit of choices visible and immediate.

Make good choices easy: Place fruit at eye level rather than banning junk food.

Leadership Application

Leaders can encourage positive behaviours by redesigning processes, policies, or environments in subtle but powerful ways.

Example: Instead of mandating wellbeing programs, make participation the easy, default option.

Nudges are especially effective where compliance and motivation are low, but freedom of choice is important.

Criticisms & Cautions

Can be seen as paternalistic (“libertarian paternalism” is the authors’ phrase).

Effectiveness depends on trust — if employees sense manipulation, nudges backfire.

Works best when combined with transparent communication, not as a replacement for it.

Why Useful

Provides a non-coercive way to influence behaviour.

Can be applied in everyday organisational life: onboarding, health & safety, ethics, sustainability, or workplace culture.

Emphasises designing systems rather than trying to “fix” people.

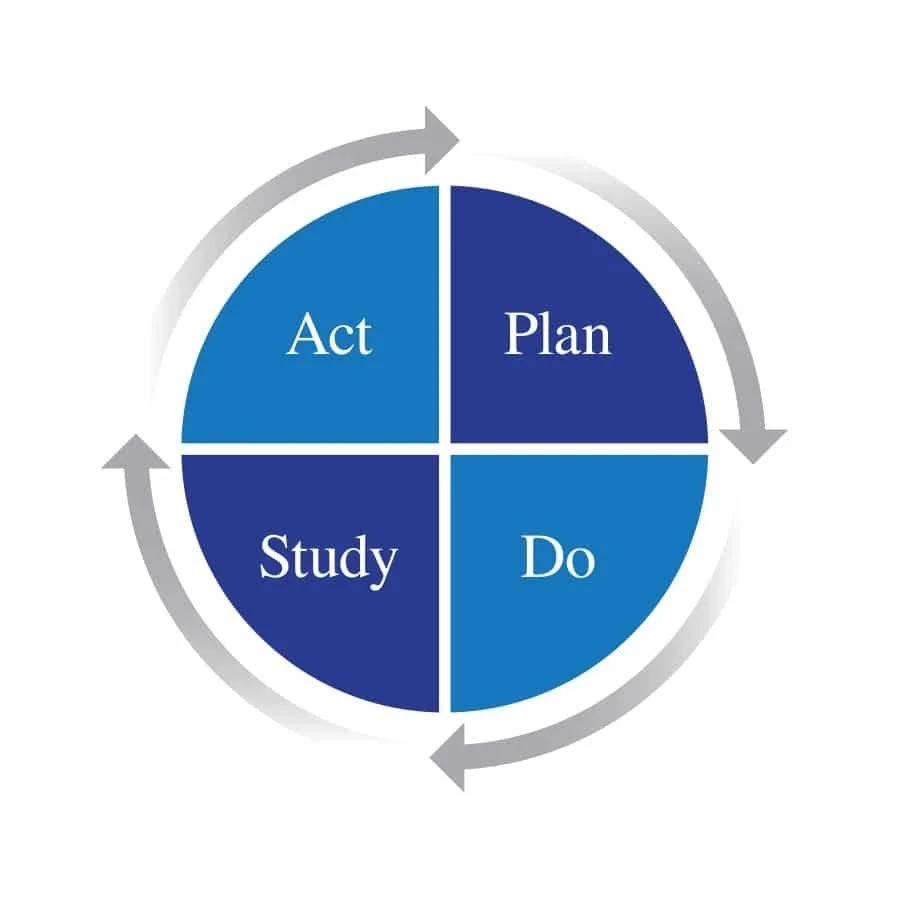

6. PDCA cycle - Deming Wheel

W. Edwards Deming developed the Plan - Do - Check (Study) - Act cycle, also known as the Deming Cycle or the Deming Wheel, which became the backbone of Kaizen, Lean, and modern continuous improvement systems (see below). The PDCA cycle is a widely used method in change management for implementing continuous improvement and driving organisational change effectively.

PDCA is a powerful operational / process improvement tool, best used for continuous improvement, quality management, and incremental change. It builds a culture of learning and refinement.

Think of it as a supporting method: while OD frameworks give the big picture of what needs to change, PDCA gives a practical loop for implementing, testing, and embedding those changes.

Here’s a breakdown of each phase of the PDCA cycle in the context of change management:

Plan: Businesses assess the need for change and establish clear objectives and goals. They develop a detailed change management plan, outlining strategies, resources, and timelines while also securing support from stakeholders to ensure alignment and commitment to the proposed changes.

Do: Businesses implement their change management plan, execute activities, communicate with stakeholders, and support employees with necessary training. Progress gets closely monitored to ensure adherence to timelines, and regular communication addresses any concerns or questions stakeholders may have.

Study / Check: Businesses evaluate the progress and impact of the change initiative by monitoring key performance indicators and analyzing deviations from the planned outcomes to understand their causes. This phase offers valuable insights into the effectiveness of change management strategies and identifies areas for improvement.

Act: Businesses take corrective actions based on findings from the check phase, adjusting the change management plan and integrating successful changes into standard procedures. This phase ensures continuous improvement by addressing issues and updating strategies based on lessons learned.

The PDCA cycle is a loop. After the Act phase, start again with the Plan phase to keep improving or tackle new problems. This cycle helps organizations stay flexible and make their change management better as things change.

Usefulness for leaders:

Best for: Continuous improvement, embedding a culture of learning, testing pilots.

Complementary Role: Works well when paired with broader OD frameworks to diagnose what to change, and PDCA to implement how to change iteratively. See our resource on organisational development frameworks for other OD models that are best for transformational or cultural change — guiding leaders through major shifts in strategy, identity, or structure.

Deming, PDCA, and Japan’s Rebuilding

W. Edwards Deming (1900–1993), was an American statistician and management thinker, who played a major role in post-World War II Japan’s industrial transformation.

After WWII, Japan’s industry was devastated. Its goods had a global reputation for being poor quality, “cheap imitations.”

Japanese leaders invited Deming (early 1950s) to help rebuild their manufacturing and economic systems.

Deming introduced statistical process control (SPC), quality improvement principles, and the PDCA Cycle

Deming’s Key Contributions in Japan

PDCA as a discipline of continuous improvement

Encouraged Japanese managers to treat every process as improvable through iterative cycles.

Focus was not just on fixing problems, but on systematically learning.

Shift in management philosophy

Urged leaders to stop blaming workers for defects and instead improve systems.

Quality became a management responsibility, not just a factory-floor issue.

Education of executives and engineers

In 1950, Deming lectured hundreds of Japanese engineers, managers, and executives.

His famous “Deming Lectures” were broadcast widely, influencing an entire generation of leaders.

Birth of Kaizen and Total Quality Management

The PDCA mindset merged with Japanese cultural values of discipline and teamwork, evolving into Kaizen (“continuous improvement”).

This became the foundation of Toyota Production System and modern lean manufacturing.

Recognition in Japan

In 1951, Japan created the Deming Prize, one of the most prestigious awards for quality management, still awarded today.

Impact

By the 1960s–70s, Japanese products (e.g., cars, electronics) were becoming world-leading in quality.

Toyota, Sony, Honda, and others credited Deming’s teachings as pivotal.

PDCA cycles helped embed a culture of disciplined experimentation and systemic improvement.

Why Change efforts most often fail:

Photo by Jared Erondu on Unsplash

Error # 1: Not establishing a great enough sense of urgency

Error # 2: Not Creating a Powerful Enough Guiding Coalition

Error # 3: Lacking a Vision

Error # 4: Under-communicating the Vision by a Factor of Ten

Error #5: Not Removing Obstacles to the New Vision

Error #6: Not Systematically Planning For and Creating Short-Term Wins

Error #7: Declaring Victory Too Soon

Error #8: Not Anchoring Changes in the Corporation’s Culture

From “Leading Change: Why Transformation Efforts Fail” by John P Kotter(1995)

Summary of Key Steps

1. Clarify the Case for Change

From Lewin / Gleicher / Kotter: Begin by unfreezing the status quo.

Ask yourself:

Are people dissatisfied enough with the current reality? (A = dissatisfaction).

Have you painted a compelling vision of a better future? (B = shared vision).

Have you explained why the change matters now? (Kotter’s urgency).

Practical tip: Share real data, stories, and examples of what happens if nothing changes. Make the why crystal clear.

2. Build Trust and Coalitions

From Kotter / Maurer: Don’t go it alone. Create a guiding coalition of credible, respected people.

Select leaders who are trusted, skilled, and positive role models.

Be alert to Maurer’s resistance levels:

“I don’t get it” → provide clarity.

“I don’t like it” → show empathy.

“I don’t like you” → rebuild trust and relationships.

Practical tip: Be visible, accessible, and consistent. Demonstrate integrity early.

3. Engage People Early and Often

From Lewin / Kotter / Resistance Model: Involve people in shaping the change. Participation lowers resistance.

Hold listening sessions, surveys, or focus groups to surface concerns.

Tailor communication to different audiences — head (rational), heart (emotional), and trust (relational).

Practical tip: Frame change as something with people, not to people.

4. Shape the Vision and Pathway

From Gleicher / Kotter / Deming: People need both a destination and a first step.

Clarify: What will the future look like? Paint a picture, and What are the first steps we’ll take?

Use stories, images, models and examples (not just spreadsheets).

Practical tip: Break the change into visible, manageable phases.

5. Remove Barriers and Create Enablers

From Kotter / Nudge Theory: Look at the environment and systems.

Clear obstacles (e.g., old processes, silos, outdated tools).

Use nudges:

Make the desired behaviour the default.

Simplify choices.

Use social proof (show who else is onboard).

Highlight immediate benefits.

Practical tip: Ask “How can I make the right thing the easy thing?”

6. Equip and Support People

From Transition Steps / Kotter / Deming: Provide training, coaching, and peer support.

Ensure people know how to act in the “new way.”

Celebrate learning curves rather than penalising mistakes.

Practical tip: Pair early adopters as mentors for others.

7. Create Early Wins and Celebrate Them

From Kotter: Quick wins boost morale and prove change is possible.

Publicly recognise individuals and teams who take bold steps.

Use visible symbols — new practices, slogans, rituals — to reinforce momentum.

Practical tip: “Catch people doing it right” and tell their story widely.

8. Sustain and Embed the Change

From Lewin / Deming / Kotter: Refreeze new behaviours into culture, policies, and routines.

Continue to reinforce why it matters, linking successes back to the vision.

Avoid declaring victory too soon — keep pressing until the new normal is truly established.

Practical tip: Embed change into performance reviews, rituals, and onboarding.

9. Acknowledge the Human Side

From Maurer: Change involves loss as well as gain.

Recognise sacrifices, stress, and emotional costs.

Honour the contributions of those who’ve carried the organisation through.

Practical tip: Use both formal recognition (awards) and informal appreciation (thank-yous, storytelling).

Final Word

Change succeeds not when leaders push harder, but when they:

Create dissatisfaction with the old, vision for the new, and clarity on the path (A+B+C>D).

Balance rational, emotional, and relational aspects of resistance.

Shape environments that nudge people toward better behaviours.

Celebrate small wins and embed big shifts into culture.