Living with greater awareness, purpose, and vitality

Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (ACT) and the Hexaflex: A pathway toward a rich, meaningful, and values-aligned life

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is a contemporary, evidence-based psychological approach that focuses on helping people live with greater awareness, purpose, and vitality.

At its heart, ACT is oriented toward one overarching aim: living well — a life that is rich, meaningful, and aligned with what truly matters. In psychological language this is often described as flourishing. In the Christian tradition, a similar vision is expressed in Jesus’ words: “I have come that they may have life, and have it to the full.” (John 10:10)

ACT does not promise a life free from pain or struggle. Instead, it offers practical ways of relating differently to inner experience — thoughts, emotions, memories, and bodily sensations — so that we are less driven by fear or avoidance, and more guided by our deepest values.

Values and Goals: What’s the Difference?

In ACT, values are understood as the qualities of living we want to embody over time. They reflect what we want our life to stand for — the kind of person we aspire to be, how we want to treat others, and how we wish to show up in the world.

Values are not destinations to be reached; they are directions to live by.

A helpful way to think about this is the difference between a compass and a checklist:

Values are like a compass — they provide ongoing direction.

Goals are like milestones — they can be achieved, completed, or checked off.

For example:

Contrast “getting married “and “being loving”. Wanting to be loving and caring is an ongoing value; whereas getting married is a goal that can be achieved and completed. We can’t guarantee that we will find the right person and get married, but we can choose to be loving and caring at any moment.

Being loving, faithful, or compassionate are values — they can be lived out again and again, moment by moment. Getting married, changing jobs, or completing a degree are goals — they may or may not happen, and once achieved, they are complete.

We cannot always control whether our goals are reached, but we can always choose how we live in alignment with our values, right now.

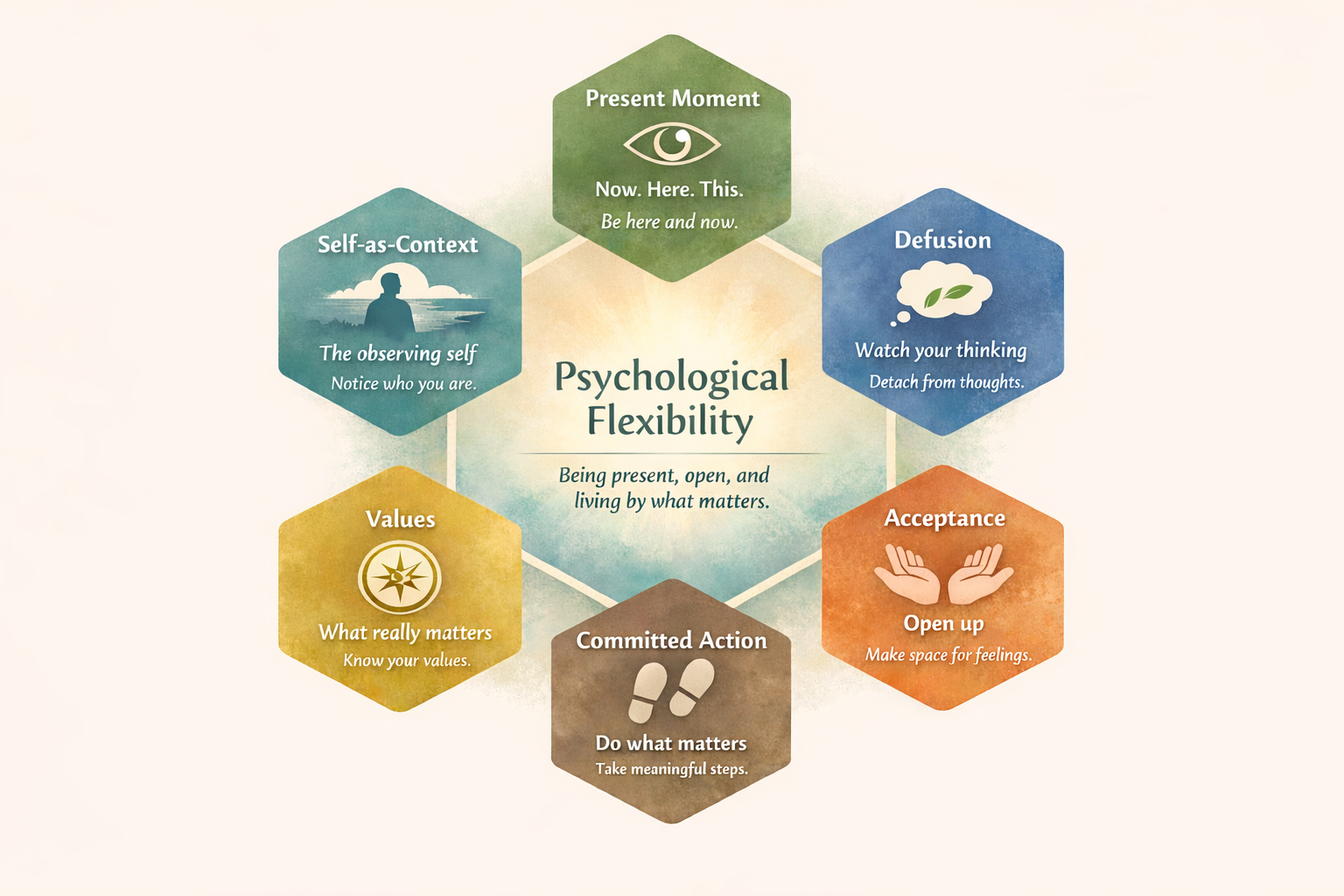

The ACT Hexaflex: Six Interconnected Processes

ACT is often illustrated using a simple visual model known as the hexaflex. It highlights six core psychological processes that together support psychological flexibility — our capacity to respond wisely and meaningfully to life as it unfolds.

These processes are not steps to be mastered one at a time. They are better understood as six interwoven facets of a single way of living.

1. Contact with the Present Moment

Now…. Here…. This

This process is about being consciously present — aware of what is happening here and now, both internally and externally.

Much of the time, our attention drifts:

replaying the past,

worrying about the future,

or running on “automatic pilot”.

Contacting the present moment means gently returning our awareness to what is actually happening — our surroundings, our body, our breathing, and our immediate experience — without judgement.

This can involve attending to:

the physical world around us,

our inner experience right now,

or both at once.

Simple grounding practices (such as “dropping anchor”) help us reconnect with the present when we feel overwhelmed, distracted, or caught in mental loops.

2. Defusion

Learning to step back from our thoughts

Defusion means learning to “step back” and separate or detach from our thoughts, images, and memories. It means Watch Your Thinking and is not “diffusion”

When we are fused with our thinking, thoughts can dominate our actions.

When we practice defusion, we create a little space. Instead of getting caught up in our thoughts or being pushed around and controlled by them, we let them come and go as if they were just cars driving past outside our house, or leaves floating by on a stream, or clouds moving across the sky. Defusion refers to changing how we relate to our thoughts. See Leaves on A Stream practise… the leaves keep moving, whether we engage with them or not. Similarly, thoughts can be observed without being fought or followed.

Rather than treating thoughts as facts or commands we must obey, we learn to notice them as mental events — words, images, stories that arise in the mind. They are just thoughts.

3. Acceptance

Opening up to experience

Acceptance in ACT means making room for difficult inner experiences (sometimes referred to as darkness or shadow) — emotions, sensations, urges — rather than struggling against them.

This does not mean approving of pain or resigning ourselves to suffering. It simply means allowing experience to be present as it is, without unnecessary resistance.

Often, it is the struggle with pain — the pushing away, shutting off, numbing, or avoidance — that causes the greatest distress.

When we soften around experience, we often find we have more capacity to live well, even in the presence of sorrow, fear, or grief. Sometimes whilst sitting in a sacred and safe place, we can be still and allow ourselves to be aware of our pain, and to just observe and allow it to be there without us reacting. It can also be helpful to talk with a trusted companion, counsellor or spiritual director.

4. Self-as-Context

The observing self

We often think of ourselves as identical with our thoughts or emotions: “I am anxious”, “I am broken”, “I am my story”.

ACT invites a different perspective.

Alongside the thinking self (the part of us that generates thoughts and narratives), there is also an observing self — the part that notices thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

“I am bored.” Who knows this? “I am angry, sad, afraid.” Who knows this? You are the knowing, not the condition that is known”. ~ Eckhart Tolle

A helpful metaphor is a chessboard:

The pieces (thoughts, feelings, roles) move and change.

The board itself (the observing You) remains steady and spacious.

In this sense, we are not the pieces; we are the awareness that holds them. Across a lifetime, much changes — bodies age, beliefs evolve, roles shift — yet the capacity to notice and be aware remains. See When Stress Feelings Well Up for a simple practise.

5. Values

What truly matters

Values give shape and direction to our lives.

They invite us to reflect on questions such as:

What do I want my life to be about?

What do I want to do with my brief time on this planet?

What kind of person do I want to be in relationships, work, and community?

What truly matters to me in the big picture?

What do I want to stand for, even when life is difficult?

In ACT, values are sometimes called chosen life directions. Clarifying them helps orient our decisions and actions, especially during times of uncertainty or transition.

6. Committed Action

Doing what matters, step by step

Committed action involves taking practical steps — again and again — in the direction of our values.

Knowing what matters is important, but meaning emerges through action. A compass is only useful if we actually move.

Values-guided action often brings discomfort. See comfort zone. Fear, doubt, fatigue, or resistance may arise.

Committed action means continuing to act in service of what matters, even when it is challenging. This may involve:

setting goals,

learning new skills,

practicing courage or patience,

adjusting course when needed.

All actions are held lightly and compassionately, recognising that growth is rarely linear.

Psychological Flexibility: The Heart of ACT

Together, these six processes support psychological flexibility — the ability to stay present, open, and engaged with life, while acting in alignment with our values.

Put simply, psychological flexibility is the capacity to:

be present,

open up to experience, and

do what matters.

As this flexibility grows, people often report a deeper sense of meaning, resilience, and vitality — not because life becomes easier, but because they become more able to meet life as it is.

Vitality, in this sense, is not about feeling good all the time. It is about being fully alive and engaged, even in moments of pain or loss.

This understanding of flourishing resonates strongly with broader wellbeing research, including the work of Martin Seligman, and with long-standing spiritual wisdom that speaks of a deep inner “well-being of the soul”.

Acknowledgements and Further Reading

This resource is informed by contemporary ACT literature and public educational materials, including:

ACT educational resources and practitioner summaries

Contextual behavioural science overviews

Positive psychology research on flourishing and wellbeing

For readers wishing to explore further, reputable introductory resources include:

contextualscience.org

positivepsychology.com

actmindfully.com.au